By sharing what the philosophical roots of my research are, I hope to give a sense of what motivates me and what questions I like to ask. These are the longstanding questions that I would like to explore through my lab.

tl;dr – My research vision is to build robots’ physical bodies in dialogue with human communities by (1) directly designing the geometry of the materials that make up robots and (2) using design justice as a tool to include all voices in the robot design process.

In sci-fi, we imagine robots to be close companions to humans, living and working alongside us. However, real robots are quite far from this goal, including high-profile accidents such as a surveillance robot running over a toddler in 2016 or a chess-playing robot breaking a child’s finger in 2022. I argue that this is because current robot bodies are not well-suited for the environments that we place them in.

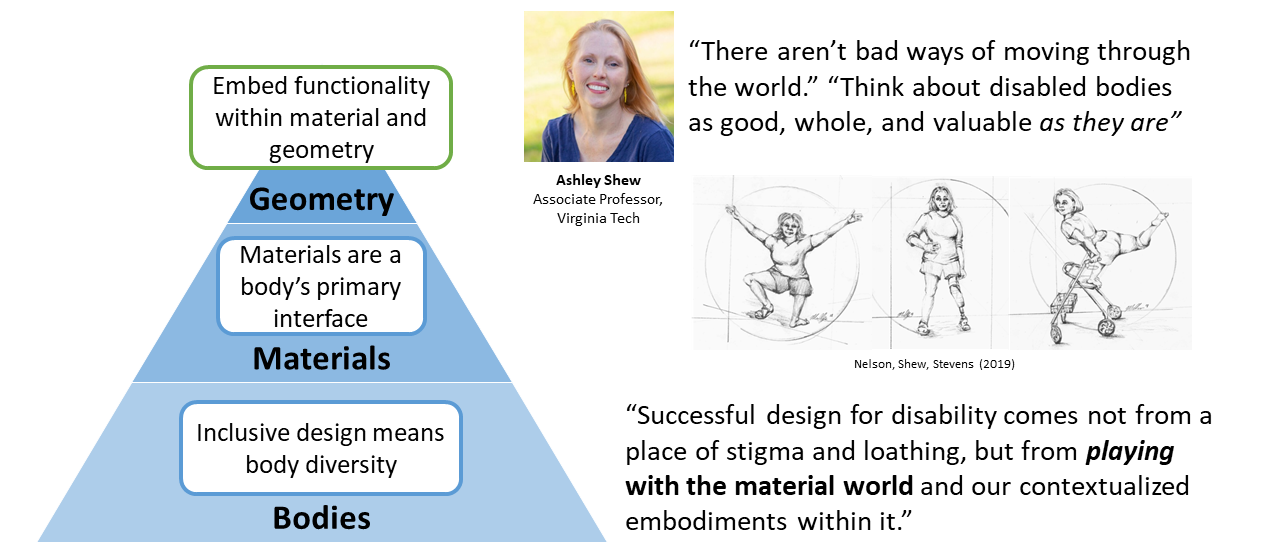

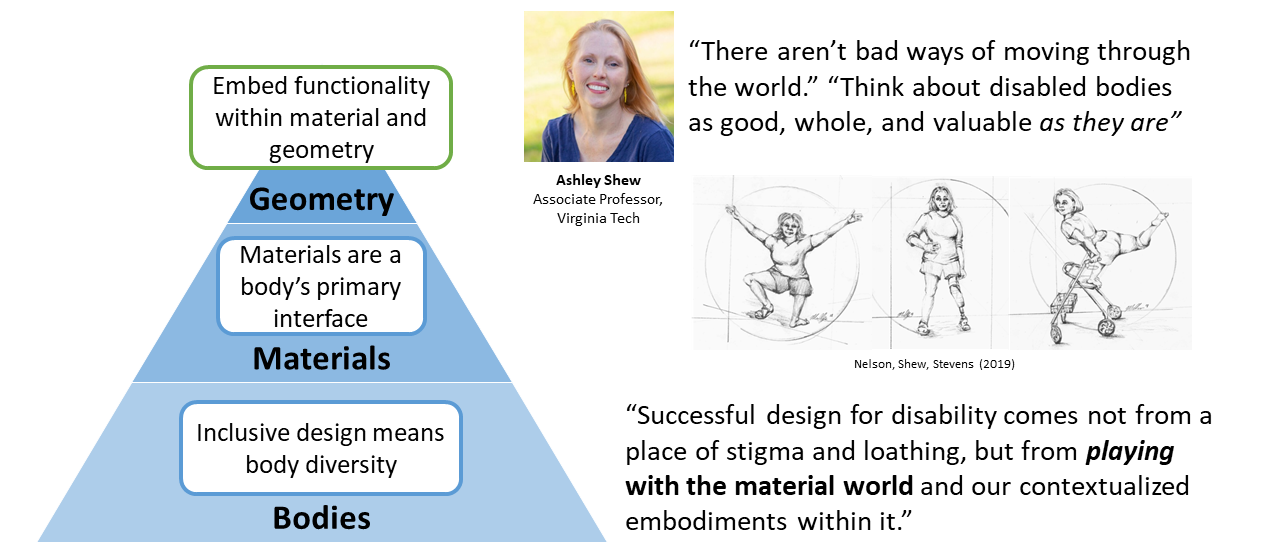

This belief is directly in line with what disability activists have been campaigning for. Although disability is often viewed as a medical impairment, current scholarship suggests we view disability under a social model instead. In this lens, disability is instead viewed as a “misfit” between the disabled person’s needs and the social built environment around them. To resolve this misfit, we need to consider

These questions can be directly applied to our understanding of robot bodies. In the previously mentioned accidents, we note that the rigid, inflexible bodies and controls of those robots made them inappropriate for the crowded, unpredictable environments they were deployed in. How can we further apply lessons from disability studies to change how we design robot bodies?

To answer this question, I take strong personal inspiration from disability studies scholars like Ashley Shew, Aimi Hamraie, Sara Hendren. These scholars highlight that design for disability must come from "playing with the material world and our contextualized embodiments within it". Instead of valuing only a single default way of moving through the world, we should celebrate the body diversities that exist and investigate what environments amplify or hinder those bodies.

For me, I like to play with materials and their geometries to make new bodies. Materials are a body’s primary interface to the world, encoding both technical constraints (ex. brittleness) and social values (ex. cuddliness). Disabled designers have done similar play with materials, such as the intentional choices of wood, glass and colors in DeafSpace architectural design or adding extra grips and stiffness to objects at home for greater accessibility.

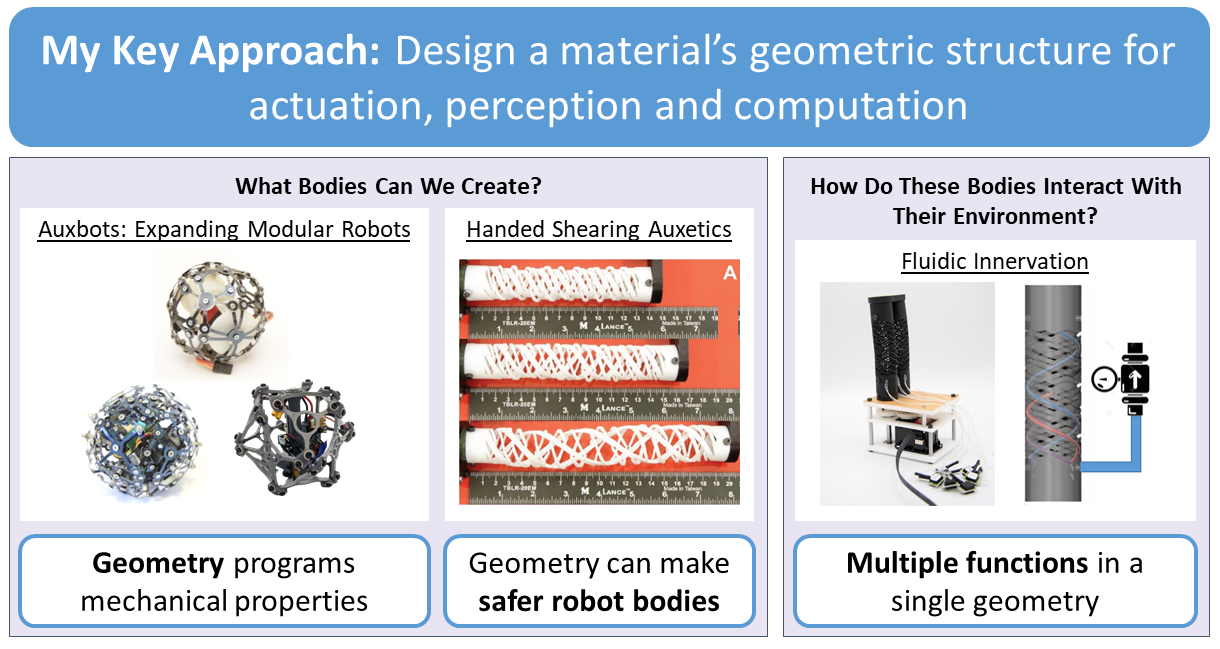

In the robotics sphere, I take this principle further through a focus on mechanical metamaterials. By changing a metamaterial’s unit cell, new mechanical properties are created. My vision is that by designing things on the geometric level, we can more clearly design a material’s mechanical properties and thus better govern how a given body will meet the world.

My key research approach is to design a material’s geometry for robotic functionality such as structure, actuation and perception. I’ve demonstrated this approach’s viability in several ways:

Since I’ve intentionally rooted my research approach in disability roots, I am very aware that my duty as a researcher lies not just in the robots that I create but in the communities where they’re deployed. From my training in the Comparative Media Studies department at MIT, I respect and value qualitative research methods from fields like design studies, critical theory and other social science / humanities fields.

There is a popular disability rights slogan: “Nothing about us without us”. What this slogan means is that equity must come from involving the people most affected by the work in the design process. While my core research area of sensor and actuator design are still at the level of basic science, translating this work into real-world applications necessitates engagement with real-world communities.

Currently, I’m interested in applications in robot manipulation and medical devices. Both of these present significant avenues for co-design and participatory design practices. Robot manipulation is the foundation for any real world deployment, especially in contact-rich, cluttered environment. Meanwhile, medical devices already exist within a complex power network between patients, clinicians, and caregivers. By collaborating with experts in design studies and human-robot interaction, I aim to ethically and communally motivate the robots we create together.